An amended North End Plan will go back to a first reading/vote by the Hoboken City Council on Wed. night February 17 at 7 pm.

Image 1: North End Redevelopment Plan: massing illustration.

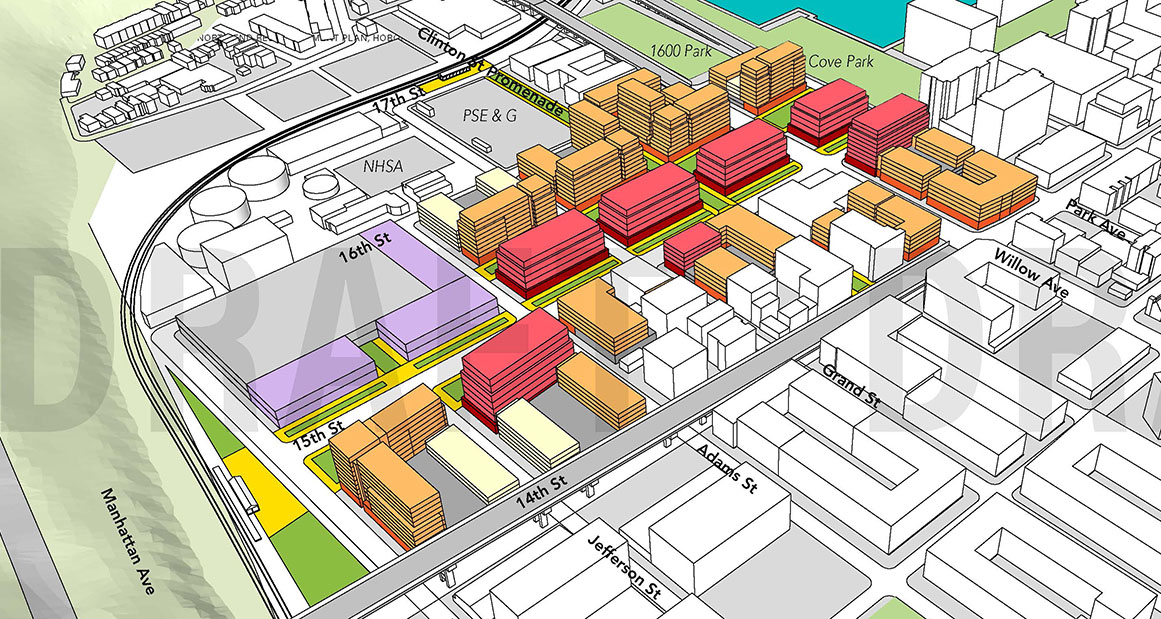

Image 2: North End Redevelopment Plan: rendering of building along 15th Street looking east.

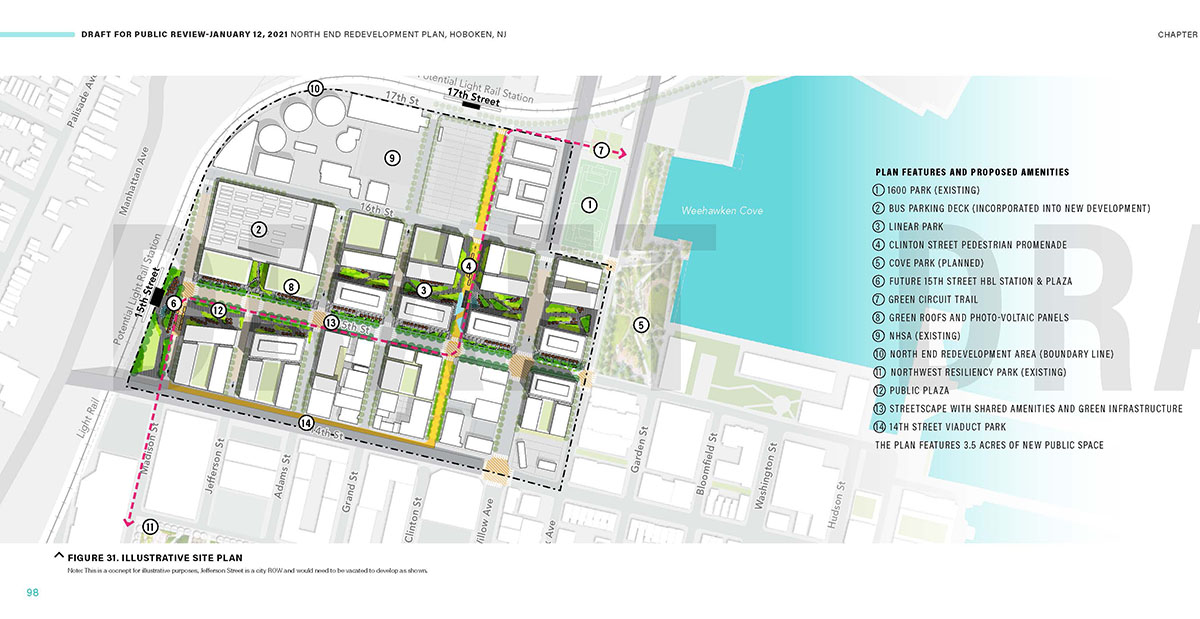

Image 3: North End Redevelopment Plan: illustrative site plan.

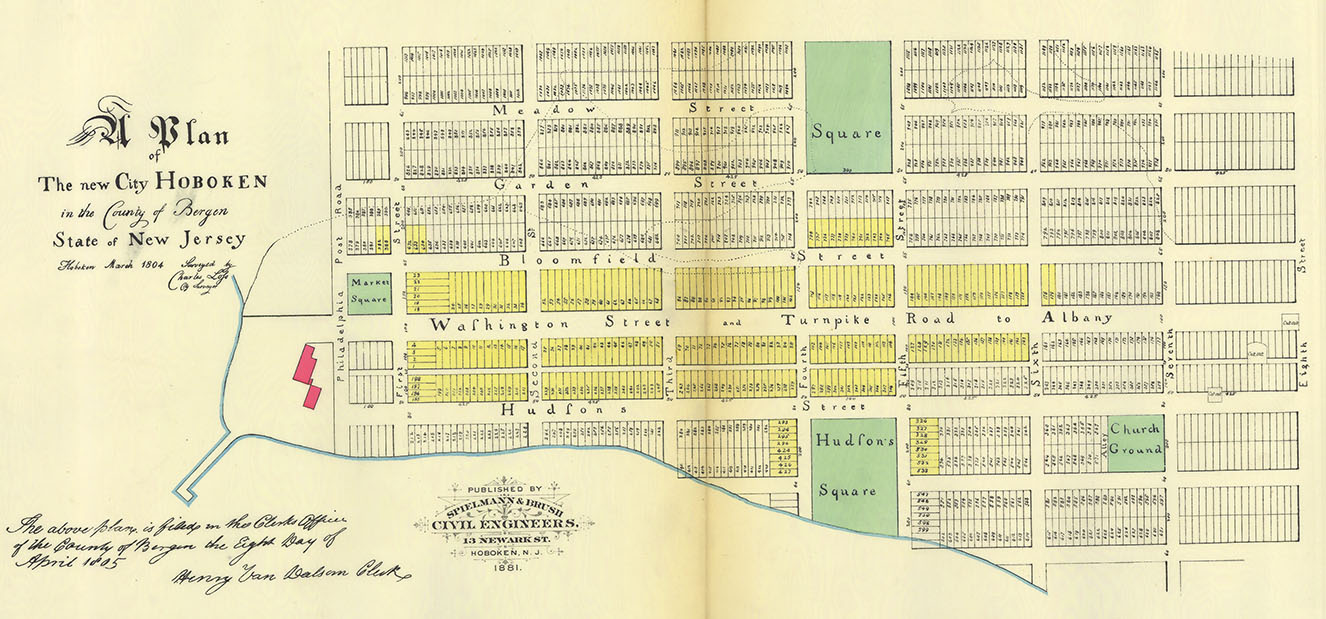

Image 4: Hoboken: Loss Map of 1804.

Ron Hine | February 1, 2021

The development of Hoboken began in 1804 when Col. John Stevens hired an engineer, Charles Loss, to come up with a plan. The Loss Map of 1804 established Hoboken’s traditional street grid. A typical block measures 425 feet long and 200 feet wide. Blocks were divided into lots typically 100 feet deep and 25 feet wide for private development. This original plan has shaped the development of Hoboken over the past two centuries, defining its character as an urban village built at a human scale. The 1804 plan included Hoboken’s first public parks, Church Square Park and Hudson Square (later renamed Stevens Park), both clearly delineated by the streets that surround them.

One of the saving graces of Hoboken’s North End is that the original, traditional urban street grid remains intact. Thus, future development will take place on typical Hoboken-size blocks. But a colossal failure of the City’s recently unveiled North End Redevelopment Plan is its open space plan. The plan claims to be providing three and a half acres of public open space. Most of this land will be private, not public. The only open space clearly delimited within the street grid is the 15th Street Light Rail Plaza.

Especially problematic is the open area that extends through the interior of four blocks between 14th and 15th Streets. The backs of private buildings abut the land making them, in effect, the backyards of private buildings. Private control of this property will likely invite ingenious ways for the owners to thwart its public use.

Historically, local government attempts to create “public” space on private land have led to a string of failures. In the 1980s, when seeking approvals from the planning board, a developer agreed to provide a small public park at the corner of Newark and Garden Streets. This space is fenced off with a locked gate. Attempts over the years to make this area open and accessible to the public have failed.

The State of New Jersey requires developers along the Hudson River to build a 30-foot public walkway at the water’s edge. However, the municipal governments of Jersey City, Weehawken, West New York, North Bergen and Edgewater failed to extend their public streets to the waterfront. As a result, the walkway is often difficult to access and is situated with backyards alongside it, creating a built-in conflict and diminishing the intended public nature of this space.

The Shelter Bay Club erected a fence to keep out the public despite granting an easement to the NJDEP for the 30 foot public walkway.

Back in the 1990s in Edgewater, several vacant units at the Shelter Bay Club were vandalized. In response, the owners put up a fence blocking off the 30-foot public walk. The New Jersey Department of Environmental Projection (NJDEP) took the Shelter Bay Club to court. It took years of litigation before the courts ruled in the NJDEP’s favor and forced the owners to remove the fence.

At Lincoln Harbor in Weehawken, the state-required walkway traverses the interior of the Riva Pointe pier. At the entrance there are steep steps and an imposing gated entrance. It is a rare event for the public to use this “public” walkway or even recognize that it exists.

The gates at Riva Pointe send a message that this is private. Yet the “public” Hudson River walkway actually extends through this project to the end of the pier.

Unlike its neighboring Hudson River towns, Hoboken has front doors facing the street and the waterfront park. There are shops, restaurants and other commercial spaces at the ground floor level that help to bring life and activity to the street and the waterfront park. The buildings that face the street and the park play an important role in defining the character of that public space.

On April 18, 2017, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer released an Audit Report on the City’s Oversight over Privately Owned Public Spaces (POPS). Stringer’s office inspected all 333 POPS locations in New York City and found 182, more than half, failed to live up to their agreements. In some cases the promised amenities simply did not exist; in others, they were non-functioning. Often restaurants expanded their seating areas usurping or blocking entry to promised public areas. The report states: “Currently property owners are benefiting financially from approximately 23 million square feet of additional (bonus) floor area in their buildings in exchange for providing POPS at 333 locations in New York City.”

There are other potential problems with the North End Plan. Without the proper design guidelines in place or clearly defined lot sizes, whole blocks could be taken up with hulking, monolithic structures filling up whole blocks. This has been one of the failures of Hoboken’s waterfront development. The variety of buildings and architectural styles lining Hoboken’s historic streets imbue the town with its neighborhood charm. This ambiance is unlikely to be replicated with the current North End Plan. A preponderance of ten and twelve story buildings could also serve to contradict the human scale found throughout most of Hoboken that is so popular with local residents.

The City of Hoboken initiated the North End Redevelopment Plan twelve years ago. On January 27, 2021, the Hoboken City Council voted on first reading to approve the plan developed by WRT, formerly known as Wallace Roberts & Todd, the firm that was responsible for developing the controversial Railyard Redevelopment Plan at the south end of town.

Related article

Meet me at the Plaza by Jerold Kayden New York Times op-ed

Related Links

Half of NYC owners fail to live up to public space agreements

What do Zuccotti Park and Hudson River Walkway have in common?

Will Hoboken Shipyard’s Pier 13 bring bad luck for public access?

With demise of Google’s plan, Toronto has opportunity to create a truly public lakefront

Liberty Harbor North based on tenets of new urbanism

The urban design principles that make for successful waterfronts

Hoboken’s original plan and first parks established in 1804

Architect Craig Whitaker’s reflections on what makes waterfronts successful