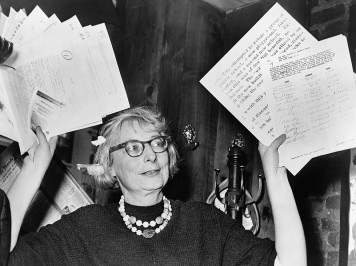

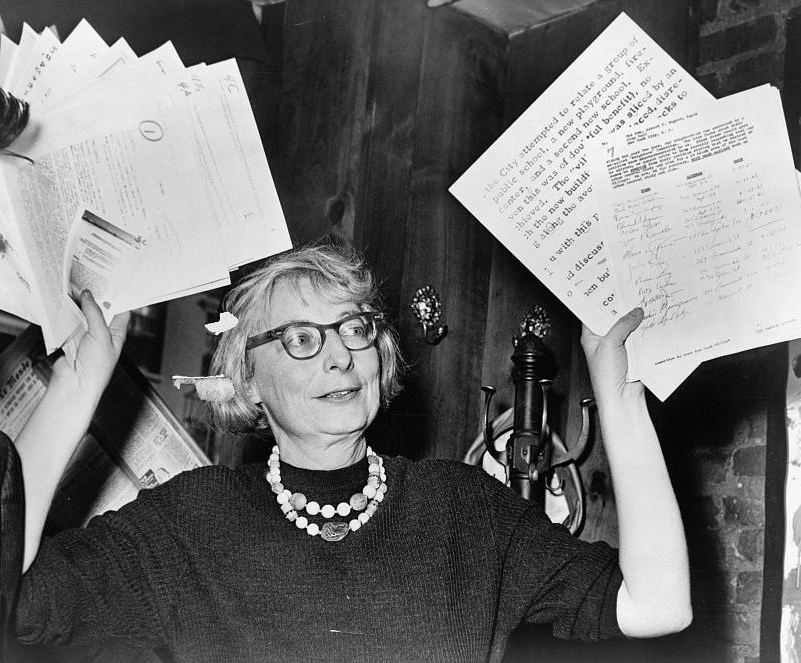

Her book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, has influenced generations of urban thinkers and city planners

Jane’s Walk Hoboken 2025 will take place on Saturday, May 3 at 10 a.m. Click link to register.

Ron Hine | FBW | April 28, 2024

I read Jane Jacobs’ seminal book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, about eight years after it was published in 1961. Like so many who studied city planning and thought about urban issues, it had a profound impact on me. I was in graduate school at the University of Pittsburgh, my first time living in a major urban area. The following year, I moved to Hoboken, on the opposite shore of the Hudson River from Manhattan.

In 1990, I helped found the Fund for a Better Waterfront (FBW) that created a Plan for the Hoboken Waterfront. This began for me an immersive experience in what constitutes the best thinking and best practices in urban design and city planning. 1961 was a long time ago, but Jane Jacobs laid out the principles that made for successful urban communities and her thinking helped to guide us through our own planning process and helped us understand why her influence is still so relevant today.

In celebration of her May 4th birthday, over 400 communities around the world will sponsor a “Jane’s Walk.” On that day, I will be leading a Jane’s Walk tour in Hoboken subtitled, “Seeing Hoboken through Jane Jacobs’ Eyes.” This will be an opportunity to share what I have learned about planning and development over the years. Jane Jacobs would love the old, densely populated neighborhoods of Hoboken with their mix of residential and retail uses, and variety of architectural styles. She would also be a severe critic of the redevelopment in Hoboken of the 1950s and 1960s that represented the failed planning practices of that era.

I just finished reading her biography, Eyes on the Street by Robert Kanigel. Jane Jacobs was born in 1916 in Scranton, Pennsylvania. She was a staunchly independent thinker. After high school, she came directly to New York City, working a variety of jobs, mostly writing and editing, which eventually led her to the magazine Architectural Forum. Despite her lack of formal training, her boss encouraged her to write about American cities. Kanigel’s book documents the evolution of her thinking as she keenly observed what made cities succeed and what made them fail.

In addition to being a writer and a noted urbanist, she was a remarkably successful civic activist. She is best known for her epic battle with Robert Moses, the subject of Robert Caro’s book, The Power Broker. She organized her Greenwich Village neighborhood to prevent Moses from running a highway through their beloved Washington Square Park. She lived with her family on Hudson Street in the West Village and successfully fought off an attempt by the City of New York to widen her street and narrow the sidewalks for an additional traffic lane.

When her family moved to Toronto, Canada in 1968, her writing career was disrupted again as she helped organize her new neighborhood to oppose a proposed highway expansion. Jacobs documented how highway building and “urban renewal” of the mid-1900s destroyed vital neighborhoods.

The first lines of Death and Life read as follows: “This book is an attack on current city planning and rebuilding. It is also, and mostly, an attempt to introduce new principles of city planning and rebuilding, different and even opposite from those now taught in everything from schools of architecture and planning to the Sunday supplements and women’s magazines.”

Early in the book, she wrote, “The stretch of Hudson Street where I live is each day the scene of an intricate sidewalk ballet.” She goes on to describe the succession of youngsters going to school, shopkeepers opening their stores — the deli, the barbershop, the hardware store — and the many who follow throughout the day both familiar faces and unfamiliar ones. It is this lively mix of people, the “eyes on the street” and the “natural proprietors of the street” as she describes it that make for a safe neighborhood and a sense of community.

“There must be a clear demarcation between what is public space and what is private space. Public and private spaces cannot ooze into each other as they do typically in suburban settings or in [housing] projects,” Jacobs explains. “The buildings on a street equipped to handle strangers and to ensure the safety of both residents and strangers, must be oriented to the street. They cannot turn their backs or blank sides on it and leave it blind.”

These are all principles that we included in our Plan for the Hoboken Waterfront. Our goal was to extend Hoboken’s best qualities down to the waterfront. The planners, architects and landscape architects that we worked with all had a deep understanding of her work. As a result, and thanks to FBW’s 34 years of advocacy, Hoboken’s waterfront today is an exceptional example of forward-thinking planning and development.

Related Links

What is the key to Hoboken’s success as a vibrant urban community?

Hoboken’s private, lifeless alleyways are an ill-conceived attempt to create public space

Who needs a car in Hoboken, the ultimate 15-minute city?

Lot size matters

Streetscapes: Dead or Alive

What Hoboken can teach us about the principles of New Urbanism

The Mapping of Urban America

Hoboken’s original plan and first parks established in 1804

A model for the North End: Hoboken’s own historic urban village

A Plan for the Hoboken Waterfront