Hoboken City Council will cast final vote on North End Plan on Wed. night March 3 at 7 pm.

Image 1: Hoboken’s turn-of-the-century five-story walkups on Washington St. south of Newark St.

Image 2: The North End Redevelopment Plan: rendering of buildings along 15th Street looking east.

Image 3: New urbanist style townhouses at Liberty Harbor North in Jersey City.

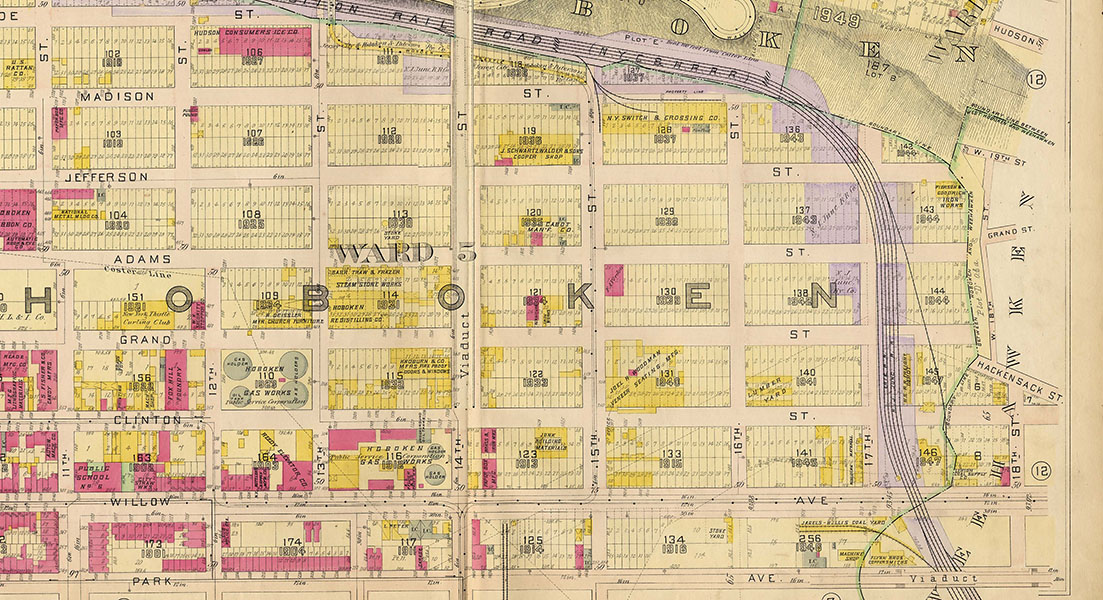

Image 4: Hopkins Plat Map of 1909 for Hoboken blocks north of 11th Street.

FBW | February 9, 2021

Hoboken developed primarily at the turn of the 20th century, thus becoming an historic urban village. With his 1804 plan, Col. John Stevens laid out its first streets and blocks creating a uniform grid. He also laid out the lots on each block, typically 25 feet wide and 100 feet deep. Throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, this plan was faithfully executed and extended to the north and west.

Rows of brick and brownstone buildings were built, as many as 32 per block, lining the front lot lines. These structures were built on a human scale, ranging from three to five stories. The result is an intimate urban neighborhood with a rich architectural heritage.

The goal of the North End Redevelopment Plan should be to replicate that special Hoboken scale and character. The goal should be to create a new neighborhood that is lively and varied. If approved as currently written, it will fail to meet these objectives.

Hoboken’s residential districts have successfully maintained much of that scale and character. Zoning ordinances limit building height, lot coverage, and rear yard setbacks that ensure that new development conforms to the town’s historic standards.

Yet these same standards are not part of the proposed North End Plan. Some buildings face the interior of blocks. Others are situated at odd angles. Lot lines are not delineated, allowing developers to build with massive footprints and blocks to be filled with monolithic structures. The bonus provisions allow for 12-story buildings throughout the 30-acre site. There is no clear delineation between public and private spaces.

To ensure open space in the North End that is truly public, one solution would be to establish a greenway along 15th Street from the Light Rail Station at Madison Street to Cove Park at Park Avenue. This would be similar to the highly regarded Ocean Parkway and Eastern Parkway in Brooklyn designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in the late 1800s. The width of the 15th Street public right-of-way could be expanded by taking a strip of land from the blocks north of 15th. This would allow for generous rows of shade trees along pedestrian pathways and protected bikeways for this six block stretch.

Instead of simply rezoning the North End, a former industrial area, the City of Hoboken has chosen to adopt yet another Redevelopment Plan. This process has dragged on for twelve years with various teams of consultants and numerous public meetings. The end result departs radically from what the heart of Hoboken represents.

In her 1961 book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs critiqued modern-day urban planning for destroying urban diversity and vitality. Her book has had a profound impact on generations of urban thinkers and policy-makers. She cited her own neighborhood, Greenwich Village in New York City as a model for a vital, urban neighborhood. Residential buildings and retail shops face the sidewalk and the street. These “eyes on the street” make neighborhoods safer. Jane Jacobs could just as well have used the streets and residential neighborhoods of Hoboken as her model.

The new urbanism movement is also based on how traditional, urban neighborhoods were planned and developed. One of the founders of the Congress of New Urbanism, Andrés Duany of DPZ CoDesign, led the planning team at Liberty Harbor North in Jersey City. They used surrounding historic neighborhoods of Downtown Jersey City for their inspiration. The first step was to lay out a traditional street grid. The plan paved the way for a diverse array of architectural styles lining many of the streets and included stoops and ground floor retail. What has been built thus far contrasts markedly from the developer-driven projects elsewhere in Jersey City.

Potentially, the 30 acres at the North End could also be an exemplary new development reflecting the scale and character of Hoboken’s urban village. It is an extraordinary opportunity. But it will only happen using the best thinking available in urban planning and design.

Related Links

Urban design flaws afflict North End Plan

North End Redevelopment Plan

Half of NYC owners fail to live up to public space agreements

With demise of Google’s plan, Toronto has opportunity to create a truly public lakefront

Liberty Harbor North based on tenets of new urbanism

The urban design principles that make for successful waterfronts

Hoboken’s original plan and first parks established in 1804

Architect Craig Whitaker’s reflections on what makes waterfronts successful