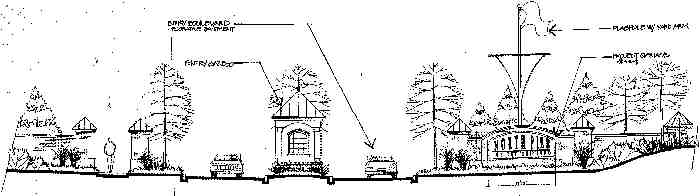

The guardhouse entrance to North Pier gated townhouse development.

The Shipyard Associates officially withdrew their proposal to build 120 luxury residential units on the North Pier in a letter dated December 19, 2000. The developer’s attorney, Ira Karasick, sent this letter to the Hoboken Planning Board citing concerns of Planning Board members and the community as contributing to their decision. The withdrawal of this development application represents a major victory for the Coalition for a Better Waterfront, Quality of Life Coalition and scores of Hoboken residents who waged a six-month long campaign to defeat pier development proposed for Hoboken’s waterfront.

Protestors wearing “stop pier development” T-shirts and holding bright-orange “stop buildings on piers” signs packed the Planning Board hearings for the North Pier project. Opponents eagerly got up to question witnesses testifying on behalf of the developers. On September 6, Elizabeth Markevitch presented petitions signed by 2500 Hoboken residents to the City Council, urging them to take action to prohibit private development on Hoboken’s piers. Scores of letters poured into the Hoboken Reporter and were sent to elected officials.

The Coalition for a Better Waterfront along with the Quality of Life Coalition and a number of individuals, also mounted a serious legal challenge to the North Pier project. Attorney Jonathan Drill of Stickel Koenig & Sullivan represented these objectors before the Planning Board. Drill presented their legal case against pier development in a letter to the Planning Board dated November 14, 2000. The major legal argument set forth in this letter emphasized that the local zoning ordinance requires that planned developments must “create a development block pattern” which by definition is bounded by streets. The North Pier project is not bounded by streets but by water. This legal position is supported by the testimony of Elizabeth Vandor, the planning consultant to the Hoboken Planning Board. On September 6, 1995, she testified before the Hoboken City Council, regarding this part of the ordinance as follows: “I should point out to you that the presence of water in the tract does not give any additional privileges or development potential to a development because the way the bulk regulations are constructed and laid out in this ordinance, water is not counted in any fashion in terms of open space or in terms of buildability of the land. All development takes place in what is called a development block which only comes into being after streets are extended onto the site.”

In 1996, the Hoboken Planning Board granted Shipyard Associates approval for a planned unit development (PUD), comprised of 1160 residential units and 63,000 square feet of commercial space. Developers of the North Pier project sought to amend this PUD approval. The project would have added 120 units on an 859 foot long pier at 16th Street. The row of townhouses on this pier would have stretched 720 feet toward Manhattan, forming a 50-foot high wall that would block views to the north of the Hudson River, the George Washington Bridge and northern Manhattan. Opponents of the North Pier project also objected to the fact that it would have created Hoboken’s first private enclave at the waterfront. The original plans showed the walled entrance to the North Pier project with a guardhouse along the private roadway leading onto the pier. The developer has tried to claim that this is his private land to do with what he wishes. The Hudson River, however, is public land that is held in trust by the State of New Jersey for the public’s benefit. Considerable confusion over this issue has arisen as private developers have taken over riparian grants, some awarded more than a century ago, to companies that depended on the Hudson River for the operation of their maritime businesses.