This article is an excerpt from Reclaiming the Waterfront, A Planning Guide for Waterfront Municipalities published by the Fund for a Better Waterfront in August 1996.

The street. It is the river of life of the city, the place where we come together, the pathway to the center. It is the primary place. – William H. Whyte, City: Rediscovering the Center

As waterfront industries abandon cities across the country, vast stretches of land have become available for redevelopment. Former maritime and manufacturing sites are being recycled for housing, commercial use and recreation. To shape this new development so that it benefits the entire community, municipalities must adopt a plan. This plan needs to be based on an understanding of some fundamental urban design principles and most especially on several principles that ensure the waterfront be clearly public.

On the Waterfront: Does it Feel Public?

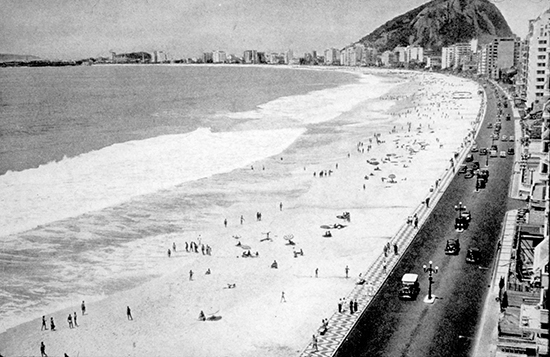

The single salient feature of a successful waterfront is that people believe it is public. This may seem like an obvious statement, but its meaning goes to the heart of the issue. On a waterfront that is undeniably public, a person can fish, stroll, swim, sunbathe, read, nap or simply be there. No one would question these activities, whether on the lakefront in Chicago, on a small strip of beach along the Chesapeake Bay in Oxford, Maryland, at the Copacabana in Rio de Janiero or along Ocean Drive in the Art Deco District of Miami Beach. These are all successful waterfronts. People of every walk of life, whether rich or poor, young or old, feel secure in their right to visit these places. People enjoy this space as their own. These waterfronts are unquestionably public.

Visitors to the Harborfront complex in Baltimore or South Street Seaport in Manhattan experience a different feeling. Even though there are often benches and other seating areas near the water’s edge at each location, one feels the need to shop, dine or otherwise financially support the commercial enterprises in the developments. There is no clear separation between what is public and what is private. As a result, even though the water’s edge may be legally designated as public open space, a person’s ability to enjoy and utilize this space is limited. It may be public but not clearly so.

Drawing the Line Between Public and Private

The common feature of the successful waterfronts like Chicago, Rio de Janiero and Miami Beach is a clear delineation between the public and private areas. In each case, a public street running parallel to the shoreline separates the public areas on one side from private uses on the other. The buildings form a wall along the street, making it clear that private development can go no further. By crossing the street toward the water, one has unmistakably entered the public realm.

Abrupt changes in topography can also delineate a boundary, as is the case with the Brooklyn Heights Esplanade in New York City. This public space is one half-level above the adjoining backyards and separated from them by a fence and planting. Most waterfronts, however, do not have dramatic changes in topography to provide a clear separation between the public and private spaces.

Front Door vs. Back Door

Just as front doors typically face the street and the public in America, the back doors open onto a different realm. The front door is where one meets the postman, puts the decorations and watches the passing parade. It is where someone meets guests and strangers. By contract, back doors face a private domain. The backyard is where families hold barbecues, build swimming pools and store things they do not want the public to see. It is not a place where someone welcomes strangers.

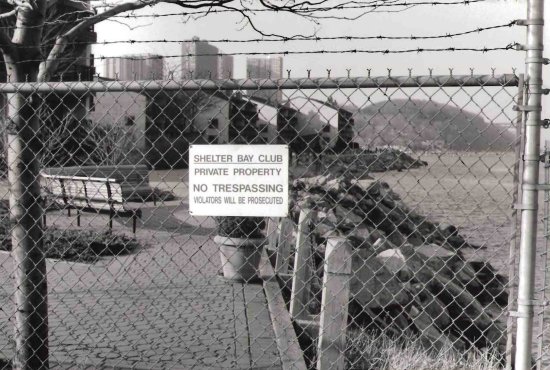

Unlike the successful waterfront projects previously cited, all those in New Jersey that have failed have had their back doors facing the waterfront. Without a street between a new development and the river, each developer has oriented his project so that a tenant’s or owner’s backyard faces the water. Where a public walkway has been constructed, an inherent conflict exists. Private backyards are thus built adjacent to the walkway, and residents of these buildings understandably do not want strangers in or even near their backyards.

A public street along the waterfront ensures that the private buildings have their front doors facing the street as well as the public waterfront beyond. Front doors create activity on the street, and also lend security to the public waterfront they face. This arrangement also ensures that the backyards of these buildings are private and secure because they face away from the public areas.

Conclusion

A municipal waterfront plan, to be successful, must follow sound principles. To ensure a truly public waterfront, there must be a clear separation between the public and private areas. A public street to and along the waterfront best serves this purpose. An extended public street system to the waterfront provides the framework for full public access. New blocks and lots within this street grid provides the framework for full public access. New blocks and lots within this street grid provide a clear set of boundaries for private development. To ensure a lively, safe and active waterfront, many front doors and windows and ground-floor retail establishments should face the waterfront. Back doors, blank walls and large parking garages should be elsewhere.