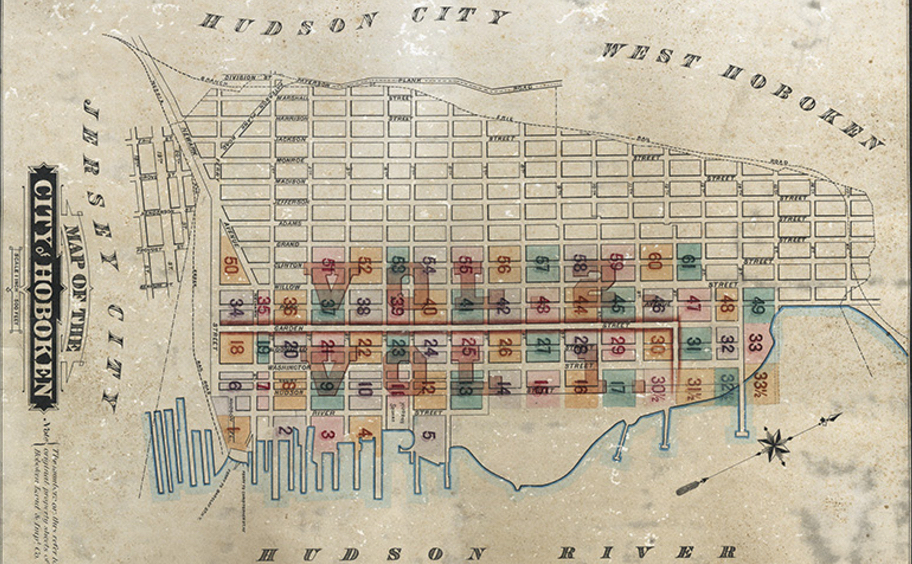

Map of the City of Hoboken from the late 1800s showing the expansion of Col. John Stevens original street grid for Hoboken of 1804.

This article is an excerpt from Reclaiming the Waterfront, A Planning Guide for Waterfront Municipalities published by the Fund for a Better Waterfront in August 1996.

Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably themselves will not be realized. Make big plans; aim high in hope and work, remembering that a noble, logical diagram once recorded will not die, but long after we are gone be a living thing, asserting itself with ever-growing insistence. – Daniel Burnham, 1907

Urban planning and, in many instances, the absence of planning have been instrumental in molding the character of American cities. During the 18th and 19th centuries, cities were subject to the most basic form of planning: the mapping of public streets, blocks and lots, and parks. Since the 1940s, public planning has been on the decline and public officials have often failed to employ this basic planning tool of mapping. As a result, many recent waterfront projects are designed to serve private interests and limit or exclude the public from the water’s edge.

Surveyors and civil engineers platted official streets and blocks and lots in American cities, thus setting the pattern for future growth. These two-dimensional layouts provided an official distinction between what was to be public — the streets, town squares, government buildings and parks — and what was to be private — the blocks and lots to be developed by private owners. The form and character of American cities during the phenomenal urban growth of the 19th and 20th centuries emanated from these official municipal maps.

Philadelphia, Savannah, and Washington, D.C. provide three of the most distinguished early examples of municipal plans. In 1681, Philadelphia adopted William Penn’s rectangular street grid encompassing five public squares. James Oglethorpe’s plan for Savannah in 1733 began with six small wards each surrounding a public square. For more than 100 years as Savannah grew, the city remained faithful to this basic planning unit. Pierre L’Efant’s 1791 design for Washington, D.C., with its diagonal streets and broad thoroughfares punctuated with monumental urban design on heroic scale and is based on a European model.

Although the design of Washington, D.C. influenced the plans for Buffalo, Detroit, Indianapolis, Madison, Wisconsin and several dozen lesser known cities, for the vast majority the gridiron pattern of Philadelphia and New York City was the model. The uniform rectangular grid became the primary basis for American city form.

In New York City, the Commissioner’s Plan of 1811 established this uniform grid pattern for Manhattan, north of Greenwich Village. This grid consisted of five major avenues running north and south and 155 cross streets, spaced 200 feet apart. The mapping of these streets, however, was not without incident. Some survey parties of the Plan of 1811 were arrested for trespassing and attacked by irate farmers. Property owners objected to having the new streets run across their land. Despite the complaints, the basic grid pattern held. Property owners eventually came to realize that it afforded them a predictable future and actually increased the value of their land.