By Ron Hine | FBW | August 4, 2016

The oyster is a bivalve mollusk, consisting of two unequal hinged shells that it forms as it grows by secreting calcium carbonate. Inside the shell is its soft body that includes a brain, stomach, intestine, kidneys, liver, and yes, as you eat it fresh, a still-beating heart. The ‘liquor’ in the shell that oyster lovers cherish is mostly oyster blood. Like fish, bivalve mollusks breathe through their gills, collecting their food and filtering the water, thus playing a highly beneficial role in the marine ecosystem. A single oyster can filter from 20 to 50 gallons of water a day.

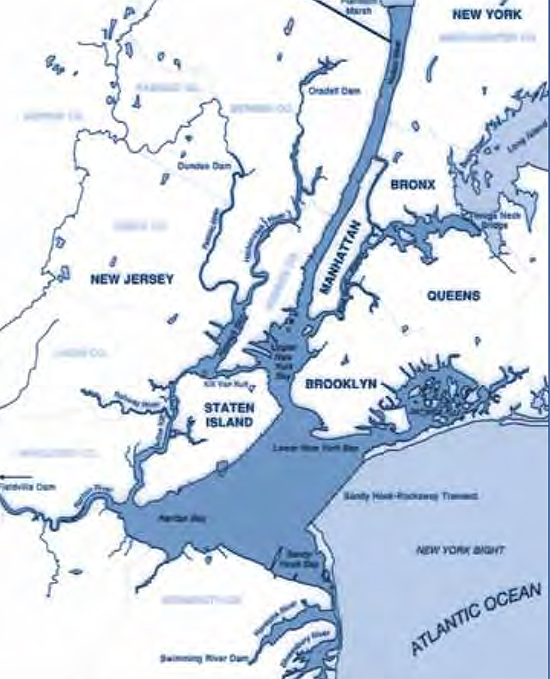

The New York Harbor is a tidal estuary. As the tide rises, the briny ocean waters fill the waterways bringing in a wealth of nutrients. The salt water travels 150 miles up the Hudson River to Troy, New York. As the tide recedes, the fresh waters flow into the estuary bringing an entirely different array of aquatic life. In 1609, when Henry Hudson arrived on his vessel the Half Moon, the waters were pristine and the estuary environment provided an ideal habitat for oysters.

In his book, The Big Oyster, History of the Half Shell, Mark Kurlansky described it as follows:

The estuary of the lower Hudson had 350 square miles of oyster beds. The beds were found along the shore of Brooklyn and Queens, in Jamaica Bay, in the East River, on all shores of Manhattan, tucked into many coves of a coastline much more jagged than it has become today because of landfills. Oyster beds also prospered along the Hudson as far up as Ossining, and along the Jersey Shore down to Keyport, in the Keyport, Raritan, and Hackensack rivers, on many reefs surrounding Staten Island, City Island, Liberty Island, and Ellis Island. . . According to the estimates of some biologists, New York Harbor contained fully half of the world’s oysters.

Kurlansky writes: By 1880, New York was the undisputed capital of history’s greatest oyster boom in its golden age, which lasted until at least 1910. The oyster beds of the New York area were producing 700 million oysters a year. As the New York City area grew, so did its appetite for oysters. There were oyster bars and street vendors selling oysters. Oysters were being exported from the New York City area across the country, to Europe and elsewhere. The world’s voracious appetite for oysters was the first step in the decline of oysters in the New York-New Jersey Estuary.

As maritime operations proliferated, New York Harbor became a major port, and the natural shorelines were filled as piers and platforms were erected, thus eroding the oyster’s habitat. As the population of the New York City area grew exponentially, raw sewage filled the waterways. By the early 1900s, the once prolific oyster community was largely decimated.

For much of the 20th Century, the estuary remained a poisonous environment for wildlife. Industries at the waterfront dumped toxic chemicals into the waterways. The most egregious example was General Electric. From 1947 to 1977, the company’s manufacturing plants dumped tons of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) into the Hudson River thus creating a superfund site.

In 1966, a blue-collar coalition of commercial and recreational fishermen formed the Hudson River Fishermen’s Association (HRFA). These pioneers were on the leading edge of environmental movement and thus began the recovery of the Hudson River and New York-New Jersey Estuary. The HRFA established the first Riverkeeper. At the same time, legendary folk singer-activist Pete Seeger announced plans to build a boat to save his beloved Hudson River. Soon after, the Clearwater was launched.

The first Earth Day, held on April 22, 1970, marked the beginning of a nation-wide environmental campaign. In 1972, Richard Nixon, who is considered by some to be the last environmental president, pushed the Clean Water Act through Congress. Since the passage of that act, the water quality in the New York-New Jersey Estuary has gradually and steadily improved. Municipalities that routinely dumped raw sewage into the waterways were forced to upgrade their wastewater treatment plants. Over time, many species of fish and other life in the estuary have returned.

The NY-NJ Harbor Estuary encompasses the waters of New York Harbor and the tidally influenced portions of all rivers and streams flowing into it.

Today, regional groups such as the River Project, the Harbor Estuary Program and the Billion Oyster Project are actively seeking to repopulate oysters in the estuary. The Billion Oyster Project’s goal is to have a billion oysters living on 100 acres of reefs by 2030, thus reclaiming the title of oyster capital of the world. Bringing back the oyster beds will further clean the waterways, restore the estuary ecosystem and provide a natural barrier to tidal surges. The Billion Oyster Project has already restored 17 million oysters in the New York-New Jersey Estuary, thus filtering over 19.7 trillion gallons of water.

If these oyster projects are to be successful, however, there are obstacles yet to overcome. Today, combined sewerage and storm water municipal wastewater systems are a major source of pollution in the estuary. During heavy rainstorms, treatment plants are overwhelmed and forced to dump raw sewage into bodies of water. Attempts in New Jersey to restore oyster habitat have been thwarted by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection that have prohibited such projects.

Related links

The Public Trust Doctrine

NJ-APA 2013 Great Places in NJ

Plan for the Hoboken Waterfont