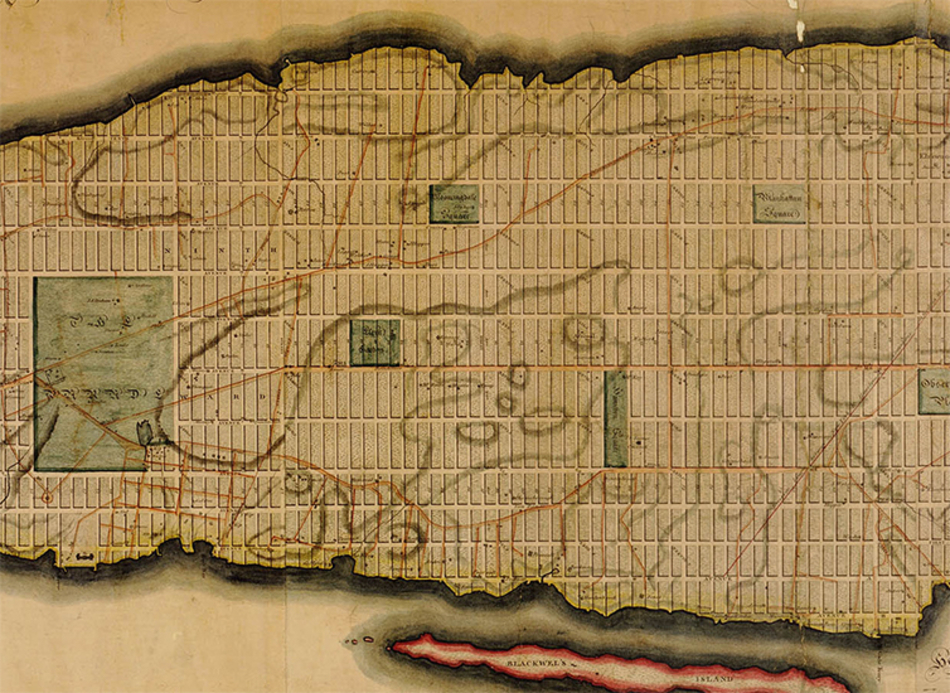

Detail from the Commissioner’s Plan of 1811 for Manhattan. This plan was laid out over a hundred years before the last parcels were developed at the northern end of the island.

This article is an excerpt from Reclaiming the Waterfront, A Planning Guide for Waterfront Municipalities published by the Fund for a Better Waterfront in August 1996.

The only legitimacy of the street is as public space. Without it, there is no city. – Spiro Kostof, The City Assembled

A vision for the waterfront begins with a plan. William Penn, Daniel Burnham and Fredrick Law Olmsted left a great legacy for the cities they helped plan. But a plan need not be elaborate to be successful.

The key to success is for a city to take the initiative and adopt a proactive planning strategy. City governments have planning powers that can ensure the public’s right to enjoy and use its waterfront. However, many opportunities have been lost as private developers took initiative on land where local officials had failed to establish a plan. Private developers, no matter how enlightened, will not plan on the public’s behalf. It is a municipality’s responsibility and obligation to promote the public interest through planning.

Mapping and Platting

The first step in the planning process is to map and plat. This act determines what is public and where private development can take place. Cities and towns have always had the right to map and plat any and all land within their own boundaries. New York City’s plan of 1811 established Manhattan’s grid over a hundred years before the last parcels were developed at the northern end of the island.

In New Jersey, the right to map and plat is codified in the state’s Municipal Land Use Law, which gives the planning board and governing body of each municipality the right to create a master plan and to promulgate and amend an official map. Municipalities in New York State are also specifically empowered to plat their land into building parcels.

In each state, a municipality’s official map has particular bearing upon its waterfront because it locates streets and public parks. Thus, even in the absence of a master plan calling out different uses and densities, a map can be used to delineate streets leading to the waterfront, and more importantly, a street along the waterfront to create the boundary between the public and private areas. In many municipalities these new streets will logically be extensions of an existing street grid. The Plan for the Hoboken Waterfront developed by the Fund for a Better Waterfront provides a clear example of how this can be done.

Mapped streets need not be immediately constructed. They may for many years be only dotted lines on an official map-what planners call “paper streets.” The streets become real only as the property abutting them becomes developed. Yet in the interim these lines remain powerful tools for shaping a developer’s thinking. A grid of paper streets in a waterfront zone already slated for redevelopment will, by its very nature, define the scale and character of any redevelopment that takes place down there.

Most importantly, “paper streets” assure people that they will have access to the waterfront at locations consistent with the public interest, rather than the interests of the developer only.

Waterfront Costs

Waterfront infrastructure costs are traditionally a negotiated expense between a municipality and a developer. Each waterfront presents different issues. An extreme example is Battery Park City in lower Manhattan. The State of New York invests hundreds of millions of dollars to create usable land by filling in sections of the Hudson River. The state’s spending on landfill, sea walls, streets, sewer systems and parks was justified simply because the economic return on this new land could repay the initial investment.

By contrast, in many smaller municipalities there may be little capital cost require to redevelop a waterfront site. Particularly in those communities with large tracts of existing industrial land, many utilities and rudimentary street system are usually already in place. The developer, as a condition of project approval, will be expected to build any additional streets and parks. In New Jersey along the Hudson River, a developer will, of course, also be required to build and maintain a public walkway as mandated by state regulations.

Some Modest Plans

In more residential communities seeking to create a public waterfront, there may be little existing infrastructure, but at the same time public access may mean nothing more than asphalt lanes and a path along the water. In Spring Lake, New Jersey, a modest strip of grass and trees fronts the lake within a neighborhood of single family homes, thus providing an important community resource.

Along these older waterfronts and in smaller residential communities, mapping is a critically important tool. Characteristically these waterfronts have many individual owners and are developed or redeveloped only over extended periods of time, sometimes even decades. A road or path along the water, with a strip of land reserved on one side for the public, may be the only organizing feature binding together a series of disparate projects by different owners and developers. In advance of any further development, paper streets drawn on an official map can ensure that design problems don’t arise in the future.

The relatively modest costs of mapping also make it attractive because the expense is limited only to the fees of the planner and/or civil engineer laying out the paper streets and the cost of submitting these plans for approval before the town’s government body.

The Zoning Ordinance and Master Plan

Once new blocks are established by an official map, the issues of building scale, density and character can be addressed by amending the zoning ordinance. Building heights and densities should reflect the desired character of the community. Appropriate building heights, lot coverage and open space requirements allow for air and light. To encourage a variety of activities at various times of the day, the zoning should permit and encourage a variety of uses. A mix of residential, retail and commercial buildings, appropriately scaled, encourages a lively streetscape. Creating zoning that can permit “as-of-right” development eliminates the need for a city to negotiate with the developer over each proposal and eliminates what can be a lengthy and costly approval process for the builder. They city’s vision for its waterfront should also be clearly stated in its master plan, thus reinforcing yet again its mandate for a continuous public waterfront.

Conclusion

After a municipality adopts an official map with the streets, blocks and lots and a public waterfront precisely drawn, everyone will benefit. Private developers have clearly defined boundaries for their buildings and avoid potential conflicts with the community and municipality over what is public and what is private. The value of all land in the community and especially the private land facing the public waterfront will be greatly enhanced. And most importantly, the community has a permanent public asset, a waterfront park, that can be enjoyed for generations to come.