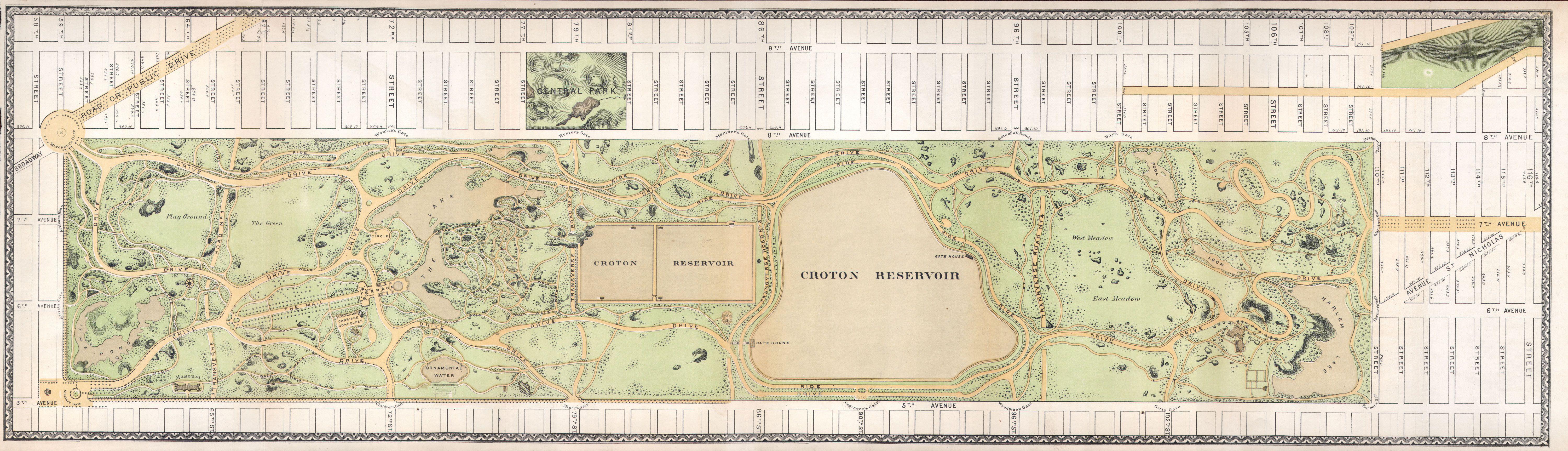

Olmsted & Vaux original design for Central Park

FBW | August 30, 2018

It is hard to imagine what New York City would be like without Central Park. The enormity of the vision that created Central Park profoundly changed the nature of Manhattan and development of urban parks across the country.

Park Advocates

By the 1840s, New York City had no parks of significant import. Andrew Jackson Downing, considered America’s father of landscape architecture, stated: “What are called parks in New-York are not even apologies for the thing; they are only squares or paddocks.” Downing argued in a series of essays that New York City needed a grand park worthy of the city’s aspirations. In one essay, he writes: “Is New York really not rich enough, or is there absolutely not land enough in America, to give our citizens public parks of more than ten acres?”

Downing’s advocacy was soon picked up in the press. William Cullen Bryant, the editor of the New York Post, wrote an editorial deploring the “very small space of open ground for an immense city.” In the New York Herald, James Gordon Bennett compared a park to a pair of lungs: “There are no lungs on the island,” he wrote. “It is made up entirely of veins and arteries.”

As the City began to fill up with buildings, the sense of urgency grew. By 1850, political candidates for mayor of New York took up the cause for a large park.

In 1851, the federal government commissioned Andrew Jackson Downing’s firm to lay out the grounds for the Capitol, the White House and the Smithsonian Institution. A year earlier, Downing brought an architect from England, Calvert Vaux, to join his firm, understanding the importance of integrating building design into park plans. Downing’s influence on landscape architecture in America and the design of Central Park, despite his untimely death in 1852 at the age of 36, is unquestionable.

In 1853, the City of New York used the power of eminent domain to acquire 778 acres from 59th Street to 106th Street that would comprise Central Park. Ten years later, the park would extend to 110th Street. 1,600 people living on this land as renters or squatters were evicted along with a school and three churches.

The Greensward Plan

The newly formed Commissioners of Central Park sought to hire a superintendent to begin the process of preparing the land for a park, clearing underbrush, demolishing abandoned structures, draining swamps and blasting out huge outcroppings of rock. Frederick Law Olmsted had no degrees or formal training in landscape architecture. He had an eclectic work history as a deckhand on a merchant ship, a farmer and a journalist. Nevertheless, he lobbied for the position and was hired in 1857.

That same year, the Board announced a competition, open to the public, to submit a design for Central Park. The design had to include a prospect tower, exhibition hall, a parade ground, a formal garden, large fountain, three playgrounds and four separate roads traversing the park. The budget was set at $1.5 million.

Calvert Vaux, having lost his business partner and the most logical candidate for designer of Central Park, Andrew Jackson Downing, approached Olmsted to work on a submission for the design competition. Vaux’s interest in Olmsted was primarily for his knowledge of the site, not for his design skills that were as yet untested.

Vaux and Olmsted set about their plan for Central Park, described in Justin Martin’s book, Genius of Place – The Life of Frederick Law Olmsted:

“The pair wanted to avoid a classic grand promenade, stretching past formal gardens and traveling under marble archways. Such opulent touches smacked of European-style royalty. A short walkway would achieve an intimate scale, proper to the common person ‘who in the best sense is the true owner’ of the park, as Olmsted put it. . . Everywhere their plan called for trees, trees, and more trees.”

They called it the Greensward Plan. An ingenious aspect of their proposal was to submerge the roadways crossing the park. The roadways were screened with dense plantings and bridges allowed pedestrians to pass over the traffic below. Of the 33 submissions, Vaux and Olmsted prevailed, sparing the park from other proposals that ranged from formal and bizarre to mediocre.

Olmsted, it turned out, had a genius for landscape design and he was a keen observer. He had been deeply influenced by Downing whose periodical, Horticulturist, he read. His exploration of European parks resulted in Olmsted’s publication of Walks and Talks. Olmsted was especially taken by Birkenhead Park, completed in 1847. It was the first British park built at the public’s expense. Prior to this all parks had been created and held privately. Of Birkenhead Park, Olmsted wrote: “Five minutes of admiration, and a few more spent studying the manner in which art had been employed to obtain from nature so much beauty, and I was ready to admit that in democratic America there was nothing to be thought of as comparable with this People’s Garden.”

Calvert Vaux designed the bridges — 36 in all, each unique — and buildings for Central Park including the Belvedere Castle and the original Metropolitan Museum of Art building. Central Park looks like a natural landscape but in fact was a major engineering feat. More than 10 million cartloads of material were removed. Four million trees and shrubs were planted.

It was the partnership of Vaux and Olmsted that established one of the world’s greatest parks. Together they also designed Prospect Park in Brooklyn and the 7-mile long Emerald Necklace in Buffalo, New York. Their legacy continued throughout the rest of their lives. Olmsted’s firm later established with his sons continued for nearly 100 years, creating some 700 parks across the country.

The Value of Open Space

The cost to build Central Park in the 1850s and 1860s was $13.9 million, greatly exceeding the original $1.5 million budget. Olmsted fought bitterly with some of his superiors to justify park expenditures. Olmsted estimated that the three wards surrounding Central Park were valued at $26.4 million in 1856, a year before construction began. After completion of the park in 1873, this same property was worth $236 million. In the years ahead, the tax revenues generated more than compensated for cost of building Central Park.

Frederick Law Olmsted had to remain ever vigilant to maintain the integrity of his landscape designs with swaths of open space comprised of lawns, meadows and wooded areas. The concept behind the Central Park Greensward Plan was to provide people a place to escape the bustle of city life. Elected officials, developers and commercial operators often see “open space” and want to fill it up.

Conclusion

Downing gave birth to Central Park and landscape architecture in America. His partner, Calvert Vaux teamed up with Frederick Law Olmsted to create and execute a concept for Central Park as a natural landscape, a greensward filled with millions of trees, over 800 acres of public open space in the heart of Manhattan. Their vision in the latter half of the 1800s influenced the development of parks across the country.