By Kate Valenta | FBW | April 13, 2016

As far back as the 19th Century, the health benefits of time spent in nature were already well known. Providing a respite to working-class city dwellers was the impetus for the visionary creation of New York’s Central Park in 1858 and many subsequent city parks across our newly industrialized nation. (Trachtenberg,1980). This was the beginning of our collective understanding that green space is more than just a luxury, and that it should remain a priority for planners and policymakers. Studies that began in the 1970s traced how access to green space improves long-term health and well-being (Journal of Planning Literature, 2015), and is particularly beneficial to children from low-income families, improving their cognitive functioning (Wells, 2000), and combating what has more recently been labeled “nature deficit disorder”. (Louv, 2008) New research from Finland and Japan has proven that even short walks of as little as 20 minutes in an urban park had positive effects on mood, blood pressure and stress levels. (Journal of Environmental Psychology, 2014). At the same time, we have learned that urbanization is associated with increased rates of mental illness and depression, so countering these effects in our cities via natural experiences is of paramount importance. When the brain has a chance to rest from the over-stimulation of the urban environment, this “restorative state” boosts creativity and problem-solving skills, and improves focus. (Louv, 2008)

The established need for urban green space is also heightened within low-income communities because they lack the flexibility of more affluent residents, who have the time and financial means to escape regularly to other natural areas. For those tied close to home by necessity, local parks are often their only contact with nature. Fortunately, research has shown that one does not have to travel to remote or pristine natural settings to extract nature’s rewards. In fact, the good news for our Mile Square City is that the salubrious effects of green space are particularly significant for those living within a 3-kilometer radius of urban parkland. (Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 2006). The most important factor — especially for children, the elderly and those in poverty — is the chance to interact with local, native species of plants, birds, insects and marine habitats, to cultivate their sense of wonder and escape the immediate stresses of urban life with regularity. (Louv, 2008) Employing this kind of scientific data to underpin policy decisions offers an opportunity for Hoboken to benefit underserved residents, and all residents, while serving as a model for sound urban planning.

Those of us in the public and non-profit sectors who are committed to addressing the quality of life concerns of communities in need have an obligation to articulate soft concepts such as ‘the human need for a sense of rootedness in nature’ (Louv, 2008), making those ideas manifest through policy decisions and direct action. In the face of rising real estate costs and gentrification, Hoboken must struggle to protect the health and well-being of its underserved residents. An unfortunate consequence of the influx of affluent families in Hoboken and along New Jersey’s “Gold Coast” has been declining quality of life for low-income residents, greater income disparity, and more families living in poverty in real numbers. Since the turn of the millennium, Hoboken’s already dense square mile has swollen to accommodate over 53,000 people, including a 42% increase in low-income households, and a 66% increase in families with children under 18. (city-data.com; hopes.org) Census data covering 2000-2014 bears this out, showing population growth of over 36% in Hoboken, compared to 4.5% for NJ as a whole through roughly the same period (2000-2010). As of 2010, 11.1% of Hoboken residents and 16.5% of Hudson County residents were living in poverty, with particularly disheartening statistics for children poverty, as compared to the rest of New Jersey. Specific to Hoboken, the actual number of children in poverty below age 5 rose by over 44% in the decade between 2000 and 2010. (hopes.org) These statistics illuminate a hidden story within Hoboken’s population explosion: that along with the increase in wealthy residents, there has been a concurrent increase in low-income and underserved residents. Although it may certainly be said that everyone benefits from the presence of public parks, access to green space in urban environments is nothing short of critical for these communities.

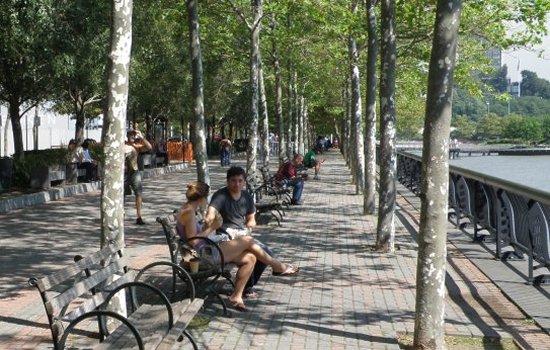

A connected waterfront park along Hoboken’s shoreline provides linear open space, open to all, undeniably public. Adjoining Hudson River municipalities have diminished the public accessibility of their waterfronts by failing to clearly delineate the public from the private.

As our population has exploded, very little new open space has been carved out. Two public parks proposed in the Southwest and Northwest sections of the city are promising as a boon to low- income neighborhoods, but still a long way from completion. Additionally, studies show that neighborhood parks often become segregated along socio-economic lines, based on the real estate values directly surrounding them (Geoforum, 2012), perpetuating unhealthy boundaries even in a city as small as Hoboken. Thus, the added value of a connected linear park along the entire length of Hoboken’s waterfront is that its benefit will not accrue disproportionately to the residents of any one particular neighborhood. It will instead provide democratic and open access, and mobility for all residents between and across neighborhoods, so that everyone can take equal advantage of our public waterfront.

Empirical evidence aside, one only has to walk the Hoboken waterfront on any given weekday or weekend to see that hundreds of residents from all walks of life and visitors from Hudson County use our parks regularly for walking, running, cycling, kayaking, fishing or simply relaxing. Local non-profits and commercial groups rely on the parks for major events, concerts, festivals and informal gatherings, and the City of course employs Pier A for beloved free community events like Movies Under the Stars, which bring the whole city together. The preservation of public lands is a worthy goal – particularly along Hoboken’s treasured waterfront – but success will be difficult to quantify, as the benefits will be reaped over time through incremental improvements in the mental and physical health of the population. This may manifest itself in lower crime rates, improved test scores or higher graduation rates from local schools, yet the effects will not be easily traceable back to the vision, years earlier, of a grand waterfront park. Just as it is hard to imagine New York City without Central Park, we hope that it will one day be hard to imagine Hoboken without a fully connected waterfront.

Citations

“Benefits of Nature Contact for Children” by Louise Chawla, Journal of Planning Literature (July 22, 2015)

“At Home with Nature: Effects of “Greenness” on Children’s Cognitive Functioning by Nancy M. Wells, Environment and Behavior (Vol. 32 No. 6, November 2000)

Last Child in the Woods: Saving our Children from Nature Deficit Disorder by Richard Louv (Algonquin Books, 2008)

“Poverty in Hoboken, Jersey City and Hudson County” from Hudson County Communty Assessment 2013, Hopes, Inc.

Related links

Col. Stevens vision for Hoboken still valid 200 years later

Editorial: A Once-in-a-century Opportunity

NJ-APA 2013 Great Places in NJ

Plan for the Hoboken Waterfont

Hoboken’s first parks established in 1804