By Wafa Dahbali | FBW | September 10, 2013

[two_fifth]

After spending the first six months of this year working for the Fund for a Better Waterfront (FBW) and learning about waterfront planning, I had the opportunity to spend two months this summer in Hong Kong, experiencing a very different waterfront and system of government. For 99 years, Hong Kong was a British colony. In 1997, this city of seven million people became a Special Administrative Region of China.

The chaotic streets of Hong Kong were overwhelming filled with an array of speeding motor bikes, cars, trams, buses and cabs. However, despite all this, every station has instructions and directions written on it so I was able to learn the city’s transportation system fairly quickly.

Stepping off the bus, one is surrounded by glowing neon signs in every direction, with swarms of people moving in every which way. Being a world traveler, I found Hong Kong to have, one of the most striking skylines in the world. Engines starting up, babbling tourists, and the tiny voice inside my head told me that there was much more to see. Walking through the Avenue of Stars (equivalent to the Hollywood Walk of Fame), visiting Hong Kong’s famous Peak, Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum, Ocean Park, Disneyland, and several other attractions created undeniably perfect replicas of the monuments that seem to matter to the world. In addition to the density, the multi-dimensional and liveliness of the interlocked skyscrapers adorned with oversized LED screens give an impression of a science fictional future city to the first-time visitor.

Throughout the 20th century, Hong Kong had and has managed to become a highly effective system of control to support an extremely dense living environment. Located in the southernmost part of China, it’s the famous center of financial power with a free market economy that is highly dependent on international trade and finance. At the core of the city, lies Victoria Harbor which is bordered by the unceasingly rising and upcoming skylines of Hong Kong Island to the south and the Kowloon peninsula to the north, which together, reflect the economic growth in built form. In order to increase the land supply, Hong Kong literally removed mountains in order to fill up the sea to accommodate the population density and further economic growth. For Hong Kong, like anywhere else in the world, the waterfront is a valuable physical asset for the future development of the City, but there is also a sentimental value attached to the waterfront – a sense of history, of ownership and a sense of belonging for many members of the public.

Hong Kong has had disputes over the filling and reclamation of their Central Harbor for more than a decade. Drawing a parallel to FBW’s mission being a leader in advocating for planned development of the Hudson River waterfront, emerging civil society organizations (or NGO’s) in Hong Kong have also fought to reclaim their political rights, promote inclusiveness to the decision making process in order to curb this trend and insist on implementing better planning and design for their harbor.

Objections have come from various sectors of the population such as Citizen Envisioning @ Harbour, an association of individuals and organizations which support a more inclusive and transparent planning process. This association promotes partnerships between government and stake holders as they demand the least amount of repossession of the waterfront that has been planned towards economic and infrastructure development. Their end goal has been to advocate for easier access to the harbor front and provide better quality of life for all its citizens, not unlike what Hoboken has experienced. However, the executive-led government has wanted to repossess more land at the heart of the harbor to continue to develop Asia’s international city. This scheme is meant to capture the chance to establish a world class harbor front environment and improve civic, recreational and cultural activity.

In contrast to U.S. waterfronts, Hong Kong land in its entirety is owned by the government and leased to private developers. By limiting the sale of land leases, the government drives the price skyward in order to support public spending with a very low tax rate. While our institutional set ups and resource allocations are quite different, nevertheless obstacles in the administration, and the power play between those that are for and against harbor repossession, a technique that Hong Kong has been doing since its inception, to enhance the limited supply of occupied land by creating new land fill (not to be mistaken for landfill) from oceans and river beds, tends to tilt in favor of their top-down government. This occurs regardless of the private sector’s opposition for further repossession and local organizations that have proactively sought out to seek alternatives in envisioning a different harbor front.

Because Hong Kong is one of the most densely populated cities in the world, parklands are highly treasured and intensively used. In planning the development of the specific waterfronts around Hong Kong, appropriate sites have been reserved for various types of land-uses including residential, commercial, industrial and open space, and for the establishment of different types of community and infrastructural facilities in order to meet the needs of the swelling population. In addition, Hong Kong has served its pedestrians well with its wide array of overpasses, sky bridges, and other ways of grade-separating pedestrian traffic.

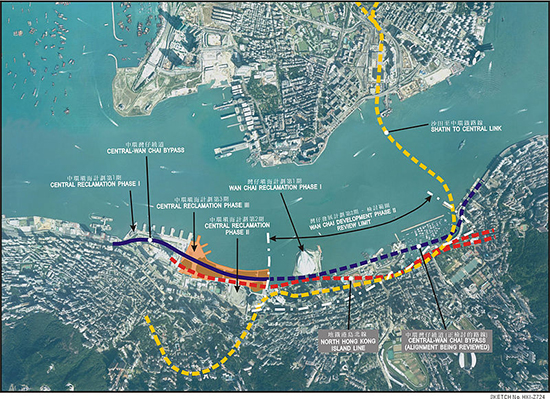

Most of the repossession has occurred in two of the most desirable locations on the harbor front which are located on both sides of Victoria Harbor. Victoria Harbor lies between the southernmost part Kowloon Peninsula and north of Hong Kong Island. This has raised a good number of environmental concerns over the years since the harbor was once the source of wealth in Hong Kong. One of the biggest controversies regarding land repossession in Hong Kong has been the “Central and Wan Chai Land Reclamation Strategy,” where Central and Wan Chai are districts located on the north western shore of Hong Kong Island.

[/fusion_text][/fusion_builder_column]

[three_fifth_last]

The Avenue of the Stars located along the Victoria Harbor waterfront in Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon on a clear day.

Left: The skyline of Central and Wan Chai Harbor front across Victoria Harbor.

Right: A sculpture tribute to martial artist and movie star, Bruce Lee is situated along the Kowloon side.

[two_third_last]

Their objective was to supply extra land towards the upgrade of their existing subway (called MTR in Hong Kong) connections and incorporate this development with existing structures. The project consisted of five phases, three for Central and two for Wan Chai. Central and Wan Chai’s repossession and redevelopment included of up to hundred hectares of land and was put towards implementing urban renewal projects, developing subway stations, airport rail lines, new piers, commercial development, government housing headquarters, extend the shoreline, and above all, alleviate traffic congestion.

According to reports from Universities and various NGO’s, the government has been criticized for several reasons surrounding the issue. First, poor planning of such projects has resulted in the seemingly wasteful development of repossessed land. The desire to protect the harbor issue can be explained in two-fold, one whether the harbor size will reduce because of repossession and whether the public has sufficient space and access to the harbor for a better quality of life and community use.

In a top-down government like Hong Kong, the growing concern has always been that public and various communities haven’t had adequate opportunities to partake in the urban design of the harbor front and the fact that the needs of elderly and disadvantaged in terms of housing have been superseded by these proposed developments, which is solely focused on catering to tourists and various types of businesses. The inability for public participation formed the crux of the current debate, where NGO’s were unable to produce and submit alternative approaches to particularly solving potential traffic issues compared to the government plan. This is has been largely due to the fact that the Hong Kong government had not released the design information.

[/two_third_last]

Related Links

[/three_fifth_last]