FBW | February 19, 2020

Hudson County, New Jersey, has a well-earned reputation for political machines and political bosses. Frank Hague was the legendary mayor of Jersey City from 1917 to 1947 who built one of the most powerful political organizations in the country. His ally Mayor Barney McFeely controlled Hoboken from 1930 to 1947. John V. Kenny followed Hague in Jersey City, first as mayor and then for several decades as the Chair of Hudson County Democratic Party.

These and many of the Hudson County elected officials that followed controlled their fiefdoms by dispensing patronage jobs, apartments in subsidized housing, and city contracts. Doling out favors and jobs was key to delivering the vote on election day. Attempts by citizens to influence municipal policy usually proved futile.

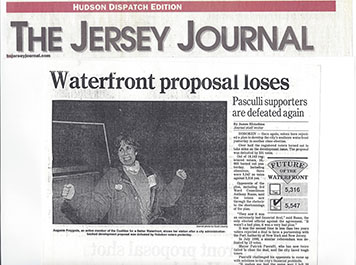

For Hoboken, this began to change on July 9, 1990. On that day, voters went to the polls to defeat an agreement between the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and the City of Hoboken to develop Hoboken’s southern waterfront. A New Jersey state statute entitled Initiative and Referendum (I&R) made this possible. The political establishment was stunned. The people who cast “no” votes felt a great sense of empowerment. This marked a remarkable reversal of fortune as peoples’ voices were heard for a change. It was democracy in action.

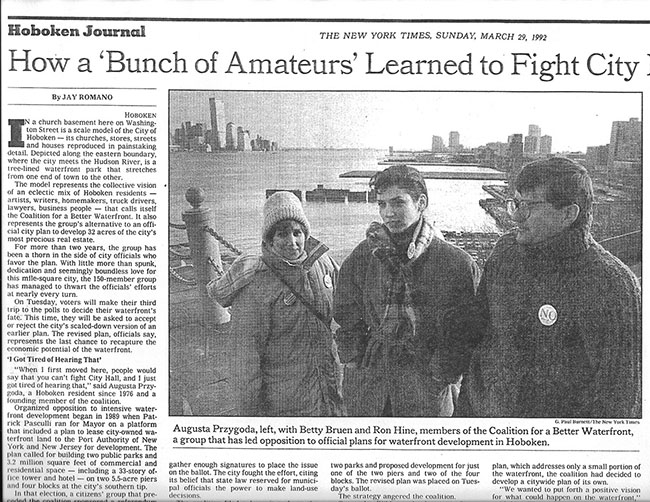

The Fund for a Better Waterfront (FBW) was formed shortly after this victory. This nonprofit group created a vision for the Hoboken waterfront expressed as a two-dimensional plan; a book, A Plan for the Hoboken Waterfront; and a 4’ by 12’ architectural model. This alternate proposal for the waterfront that included a continuous park at the water’s edge made a second referendum victory possible in 1992 that again nixed the City’s development scheme for the southern waterfront.

Public policy in Hoboken, however, continued to be driven by developers and others pursuing their private interests by contributing large sums of money to political campaigns, a practice some described as “legal bribery” also known as “pay-to-play.” In response, FBW worked with a new group, People for Open Government (POG) to push through a number of reforms, such as the Public Contracting Reform.

This new ordinance effectively prohibited professional companies with municipal contracts from making political contributions to local campaigns. POG utilized the I&R statute to place the ordinance on the ballot in the November 2004 election. The voters approved the measure by a 10 to 1 margin.

Subsequently, POG pressed the City to pass a developer pay-to-play ordinance under threat of another ballot initiative. In the years that followed, these two ordinances effectively dried up campaign contributions from professional service firms seeking municipal contracts and real estate developers with projects in redevelopment areas, thus leveling the political playing field.

In November 2007, Hoboken went to the polls to approve an Initiative that created the Open Space Trust Fund. The ordinance dedicates 2 cents per $1,000 of assessed property value each year for the acquisition of public open space. Again, the vote to approve the measure was overwhelming.

Prevailing in that 1990 referendum was no easy task. Jimmy Farina, the City Clerk, rejected the petitions and the case went to court. In Tumpson v. Farina, the City got a favorable decision in Hudson County Superior Court. The Appellate Court reversed that decision on April 23 and on July 2, 1990 the New Jersey Supreme Court also upheld the voters’ right to a referendum.

In its decision, the Appellate Court stated, “On its face, the Ordinance is one which fairly invites involvement of the public at large, for it authorizes a project whose location, size and nature will long and significantly affect the style and quality of life in the community.”

The referendum, held a week after the Supreme Court ruling, defeated the ordinance but only by a few votes. The City challenged the results but was again rebuffed by the Court.

If the Hoboken voters had not had the right under the I&R law or had lost that 1990 ballot measure, the course of history for this town would have been changed forever and FBW’s ability to influence public policy would have been severely limited. The development of Hoboken’s waterfront, like other Hudson River waterfront communities, would have been driven by developers with sound public planning relegated to a back seat.

The Hoboken waterfront today with its public park at the river’s edge is a testament to how citizens can be a force for good. In 1990, every elected official in Hoboken opposed these efforts. Today, there is 100 per cent support from the mayor and council to complete the waterfront park.

NOTE: The Citizens Campaign initially drafted the model ordinances to prohibit pay-to-play and other municipal reforms that have been utilized in Hoboken and other communities. New Jersey Appleseed has been instrumental in defending the rights of communities to use New Jersey’s Initiative and Referendum (I&R) statute. I&R does not apply to all forms of municipal government in New Jersey but citizens also have the right to petition and vote to change their form of government. Unfortunately, in response to the Hoboken referendums in the 1990s, state legislators changed the I&R law to exclude issues related to redevelopment.

Related links

How a bunch of amateurs learned to fight city hall

Giving New Jersey’s Minor Political Parties a Chance by R. Steinhagen

FairVote

Pending disaster in Hoboken’s upcoming election without majority rule

Citizen initiated ordinances bring an end to pay-to-play campaign cash

Political turmoil and pay-to-play ordinances level the political playing field

POG takes mayor and City to court for campaign finance violations

Major contributions solicited from developers and city contractors

Developers pay to play at Hoboken City Hall by writing big checks